Jasper National Park History

In the summer of 1810, David Thompson, one of Canada’s greatest explorers, became the first white man to enter the Athabasca River Valley – and hence the European history of Jasper National Park begins. The following winter, when Thompson was making the first successful crossing of Athabasca Pass, some of his party remained in the Athabasca River Valley and constructed a small supply depot northeast of the present town. Other trading posts were built along the Athabasca River, including one that became known as Jasper House, for the clerk Jasper Haws. This particular post was first established in 1813, then moved to the shore of Jasper Lake in 1829. By 1865, with the fur trade over and the Cariboo goldfields emptying along routes easier than passing through what is now Jasper National Park, the Athabasca River Valley had very few permanent residents. One settler was Lewis Swift, who in 1892 made his home in the abandoned buildings of Jasper’s House, farming a small plot of land beside the Athabasca River. “Old Swift” became known to everyone, providing fresh food and accommodations for travellers and generating many legendary tales, such as the day he held the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway at gunpoint until they agreed to reroute the line away from his property. In 1907, aware that the coming of the railway would mean an influx of settlers, the federal government set aside 5,000 square miles as Jasper Forest Park, buying all the land, save for the parcel owned by Lewis Swift. A handful of Metis homesteaders continued to live in the valley, but the land on which they lived was leased. The threat of oversettlement of the valley had been abated, but as a designated forest park, mining and logging were still allowed.

The Moberly Cabin was once home to an early settler and his family.

Mining and a Link to the Outside World

In 1908, Jasper Park Collieries staked claims in Jasper National Park. By the time the railway came through in 1911, mining activity was centreed at Pocahontas (near the park’s east gate), where a township was established and thrived. During an extended miners’ strike, the men spent their spare time constructing log pools at Miette Hot Springs, which were heavily promoted to early park visitors. The mine closed in 1921, and many families relocated to Jasper, which had grown from a railway camp into a popular tourist destination. By this time the park boundaries had changed dramatically. In 1911, the park had been reduced to two-thirds its original size, then in 1914 enlarged to include Maligne Lake and Columbia Icefield, then enlarged yet again in 1928 to take in Sunwapta Pass. Today’s borders were set in 1930, when Jasper was officially designated a national park. And what of Old Swift? Well, after working as Jasper National Park’s first game warden, he hung onto his land until 1935. The government of the day made various offers, but Swift ended up selling to a wealthy Englishman who operated a dude ranch on the site until finally selling the land to the government in 1962.

The Jasper-Yellowhead Museum is a good place to learn about local history.

Jasper Grows

In 1911, a construction camp was established for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway near the present site of downtown Jasper. When the northern line was completed, visitors flocked into the remote mountain settlement, and its future was assured. The first accommodation for tourists was 10 tents on the shore of Lac Beauvert that became known as Tent City. In 1921, the tents were replaced and the original Jasper Park Lodge was constructed. By the summer of 1928, a road was completed between Edmonton and Jasper, and a golf course was built. As the number of tourists to Jasper National Park continued to increase, existing facilities were expanded. In 1940 the Icefields Parkway was completed, linking Jasper to Banff and making Jasper National Park more accessible.

Town of Jasper

The modern infrastructure of Jasper began developing in the 1960s, but until 2002 the town site was run from Ottawa by Parks Canada. Jasper is now officially incorporated as a town, with locally elected residents serving as mayor and council members. Decisions made by the council must still balance the needs of living in a national park but also represent locals who call Jasper National Park home. On the surface, obvious visible changes of this autonomy are a new emergency services building, a new wastewater treatment plant, a new school, and improvements to an ever-increasing downtown parking problem that were in relived by the introduction of pay parking in 2021. One thing hasn’t changed, and that’s the basic premise of the town’s existence: More than 50 percent of Jasper’s 4,600 residents work in the hospitality industry, serving the needs of 2.5 million visitors annually.

More Jasper History Sources

We also have a page dedicated to Maligne Lake history.

We also have a page dedicated to Maligne Lake history.

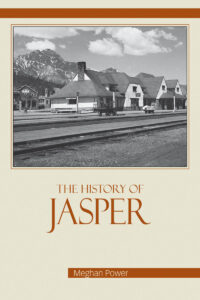

The Jasper-Yellowhead Museum is well worth visiting while in town. In print, search out a copy of Meghan Power’s History Of Jasper at local retailers. The book can also be purchased directly from Summerthought Publishing.